BIODIVERSITY 101: GUIDE FOR INVESTORS

Disclaimer: This guide was produced collaboratively by members of the CFA UK Sustainability Community and reflects the opinions, research, and insights of the contributors. The views expressed herein are those of the individual community members and do not necessarily represent the views or official stance of CFA UK. While the guide aims to provide valuable resources for investors in the biodiversity space, CFA UK does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or suitability of the information provided.

Introduction

This guide was prepared by CFA UK Sustainability Community Champions and Community Manager Aya Pariy in summer 2024.

The guide describes key considerations and the roadmap for investors to think about Natural Capital. It also refers to organisations or sources of information on certain points.

This guide’s purpose is to help investors understand how they can be impacted by biodiversity and what and how much they can do about it given the rules they have in place within their organisations (mandates, fiduciary duty etc).

“Biodiversity continues in its budding phase as an investment theme, following the 2022 Biodiversity conference and the emergence of TNFD. Biodiversity funds have recently been launched, although size, strategies and approaches still limit its adoption as a core strategy by some investors”.

Nyasha Mafoti, CFA, AVP, SSGA

“While many investors are beginning to understand the importance of climate factors, the integration of nature-related considerations into investment decisions has lagged. The efforts by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD*) could be pivotal in changing this, acting as a catalyst for incorporating biodiversity concerns into mainstream investment strategies."

Cedric Jirsell, CFA, Sustainability Analysis Director, Matter

“The positive impacts nature and biodiversity can have on climate change - offsetting emissions, building resilience, and adapting to changes in climate - is becoming clear. The need to factor biodiversity into economic decisions is unavoidable as it will soon be considered mainstream."

David Manuel, CFA, CIO, Founder, Beagle Partners

Executive Summary

This guide, prepared by CFA UK's Sustainability Community, provides investors and all finance professionals with essential insights into integrating biodiversity considerations into their investment strategies. It outlines the importance of biodiversity for maintaining resilient ecosystems and the critical role of investors in supporting sustainable practices.

The guide emphasises the significance of understanding biodiversity, measuring ecosystem health, and recognising the interdependencies between human activities and nature. It discusses the evolving regulatory landscape and voluntary reporting standards such as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD).

Additionally, it offers practical steps for investors, including initial assessments, engagement targets, and setting measurable sustainability targets.

This guide comes from community volunteer experts as they have been researching and gathering essential insights

The guide aims to enhance investors' ability to make informed decisions that contribute to biodiversity conservation and long-term economic resilience.

Contents

CHAPTER 1: Why nature and biodiversity are important

- Definitions

- Measurement

- Critical elements

- Biodiversity and Climate Change

- Humanity’s dependence on Nature – Impact & Sustainability

CHAPTER 2: What do I need to do?

- TNFD

- EU

CHAPTER 3: Who is out there to help and guide?

- Frameworks

- Standards and Boards

- Index Providers

CHAPTER 4. How to invest for biodiversity. Steps to follow, reporting metrics and examples. How to set targets

- Roadmap

- Reporting

- Setting Targets

Bibliography

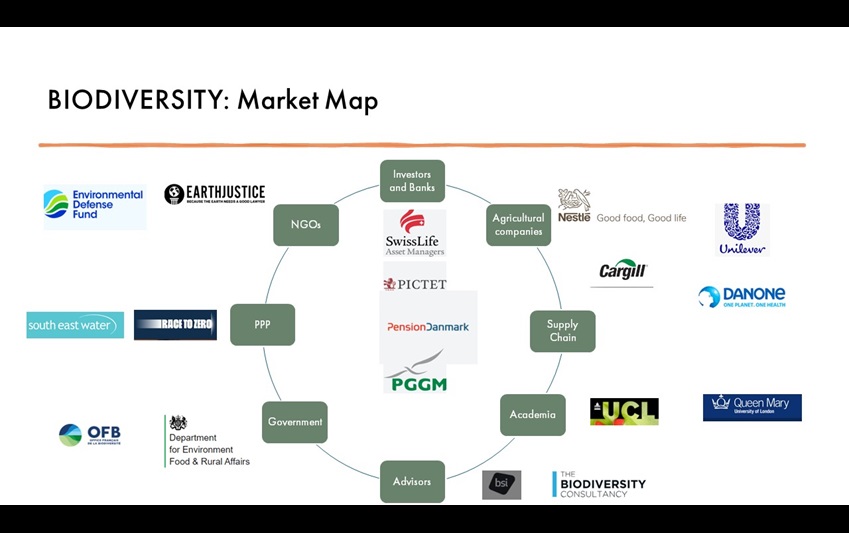

- Appendix 1: Market Map

Chapter 1: Why nature and biodiversity are important

In recent years, awareness of humanity’s dependence on nature has become more widely integrated into debates and policy discourse about sustainability. Climate change and COPs first became mainstream in shaping the discourse around sustainability, with the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) reports creating an accepted analysis of the need for change.

Somewhat under the radar, but now emerging into the mainstream, the Biodiversity COPs have been gaining traction, being integrated into policy debates and pledges of action.

The IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiveristy and Ecosystem Services) and the recent GBF (Global Biodiversity Framework) adopted at Biodiversity COP15 in Montreal in December 2022 have brought the importance of nature, and the urgency of addressing its decline, to the mainstream.

The close relationship between Climate and Nature means that the two will increasingly be considered together. Climate has had a measurable and globally recognised metric of relevance to drive measurement, management and disclosure. Nature is much more complex and local in how it needs to be measured and understood.

Biodiversity is becoming adopted as a useful proxy for the health of Nature as it is correlated with healthy and resilient nature-based ecosystems. It has become imperative to measure the health of our ecosystem. Nature plays a critical role in maintaining a stable ecosystem on a planetary level. It provides resources and services that humanity is dependent on. Thus, with the right understanding, investors can be active agents in maintaining sustainable nature.

DEFINITIONS

“Biological diversity — or biodiversity — is the variety of life on Earth, in all its forms, from genes and bacteria to entire ecosystems such as forests or coral reefs.” United Nations

“An ecosystem is a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscapes, work together to form a bubble of life.” National Geographic

Understanding the factors that increase or decrease biodiversity should allow humanity to manage its impact on Nature and ensure that the wider ecosystem remains stable, resilient, and sustainable. With this understanding, we can identify positive and negative impacts of human activity to achieve this objective.

MEASUREMENT

Biodiversity refers to the variety of species within a specific ecosystem, influenced by the local climate, terrain, and ecological conditions. The health of such an ecosystem is assessed through three

key indicators:

- Species diversity - biodiversity

- These species’ population sizes

- The continuous extent of the ecosystem’s habitat

Changes in any of these indicators can diminish or enhance the resilience and sustainability of the ecosystem.

Biodiversity (species diversity) is one of the three factors mentioned above when calculating Natural Capital. The term “biodiversity” can be used to some extent to refer to the overall health of nature. Biodiversity scores may refer to the product of these three factors. Scores tend to focus on diversity and population quantity while the extent of the biome is often an afterthought.

For example, the UK Government has developed a scoring system to address biodiversity gain/loss for policy and fiscal incentives. This guide explains how and when to use the metric. This scoring system also respects these three components and factors in the uniqueness of habitat and species presence.

CRITICAL ELEMENTS INFLUENCING AND PRESSURING BIODIVERSITY: THE EXISTENTIAL RISK

Biodiversity at a local and global level is pressured by anything that upsets the stability of a particular biome. Ecosystem diversity gives a biome a certain degree of resilience and adaptability. This ecosystem can remain sustainable if the environmental volatility and impacts are modest enough for the system to recover. If crucial species in the ecosystem are lost or displaced there is a risk of a cascade of consequences that can further impact and degenerate the ecosystem.

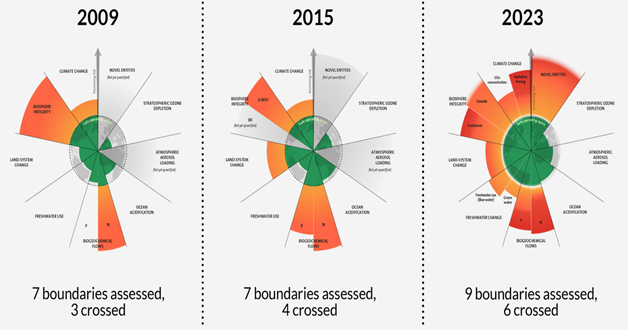

Loss of habitat, water and nutrient levels, ambient temperature, climate and pollution can all potentially be destabilising factors. It is helpful, therefore, to be aware of the and their monitoring of planetary boundaries that we are challenges the boundaries, breaks or rolls them back, is a negative or positive from a sustainability dynamic point of view. All these factors have interdependencies.

Credit: "Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023"

BIODIVERSITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE: CARBON CYCLE

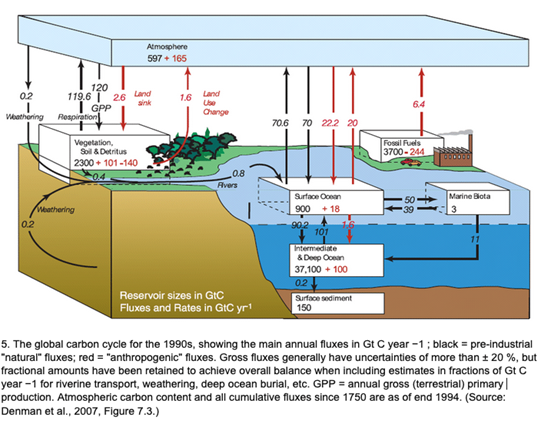

While biodiversity is linked to all these sources of pressure on the planet both in absorbing impacts and being damaged by them, the dominant influence is climate, which is now hitting critical levels of pressure. We think of man-made emissions as the cause, and indeed in terms of the net contribution to greenhouse gases accumulation and climate warming, human net contribution is dominant.

However, changes in nature-mediated carbon flows are also upsetting the system balance. There is an opportunity to be better stewards towards nature. Such stewardship is crucial to mitigate emissions from human activity and to keep the system balanced overall. It is necessary to look at the large circular flows and locked up carbon levels that have been stable enough for the ecosystem to maintain a homeostasis* to support life on earth.

Homeostasis – any self-regulating process by which biological systems tend to maintain stability while adjusting to conditions that are optimal for survival (Britannica).

The figure below shows estimates of the natural flows and stocks of carbon attributed to Nature and human activity (back in the 1990s, it's much worse now) (Denman 2007).

HUMANITY'S DEPENDENCE ON NATURE, IMPACT AND SUSTAINABILITY

Humans are not separate from nature. We are part of Nature, and therefore part of the planetary ecosystem. As a species we are now, via our activity, the dominant vector of change in the system. That means it's important to understand our role in the global ecosystem.

Humans, as an increasingly urbanised species, often regarded nature and unfettered wilderness as something “other,” distinct from their everyday reality. This mindset of human exceptionalism, where some of us believed in our superiority and ability to improve upon nature, stems from two primary sources. Firstly, it arises from our immersion in predominantly man-made environments, which disconnects us from the natural world. Secondly, it is driven by a deep-seated belief in our capability to surpass the efficiencies of natural systems.

However, there is an emerging mindset among many people where nature is top of mind. Growing awareness of environmental issues and the recognition of the intricate interdependence between humans and nature are prompting a shift in perspective.

Many individuals are re-evaluating their impact on the natural world and are increasingly adopting more sustainable and ecologically conscious lifestyles. This shift signifies a growing acknowledgment that preserving and harmonising with nature is not just beneficial but essential for our collective future.

Despite the success we have had in creating technologies to solve problems, we remain existentially dependent on Nature. If we trace the basic human needs for life and economic activity to their primary sources, it is glaringly obvious that we are dependent on Nature. More than half of the world’s total GDP, USD 44 trillion of economic value generation, is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services and is therefore exposed to Nature loss. (World Economic Forum, (2020), Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy)

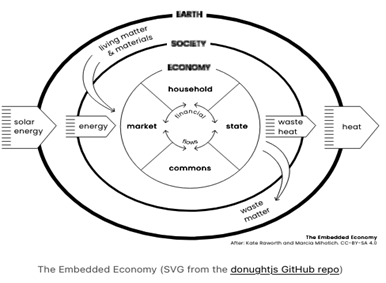

Measuring dependence is the first step in gaining awareness, understanding the risks of ignoring it and not factoring our impact on Nature into our collective actions. Neo-liberal economics often overlooks impacts not reflected in profit and loss statements, treating these as externalities. Consequently, the responsibility to address these externalities typically falls to governments, which also prioritise financial metrics and tend to act only when these externalities pose significant financial threats. However, there are schools of economics that are attempting to consider Nature and are gaining more traction. These are not new economic approaches, but they have not been historically the ones used to manage the human economy.

There is a temptation to look at the value of Nature to the economy simply in financial terms. But many of the services and products of Nature are regarded as free in financial terms. If those services are not owned or consumed by identifiable participants in the financial economy, they can be disregarded. Single materiality in financial terms as a cost or benefit for a participant fails to capture the non-financial impacts. It also fails to capture participant’s impact on the natural resource or natural capital stock that generates ecosystem’s goods and services. Double materiality also impacts externality.

Thinking systemically and more holistically about value enables a more complete understanding of the human economy’s interdependence, and therefore our interest in responsible stewardship of Nature.

For a sustainability-based economic model, we need to turn to ecological economics, which considers the flow of primary resources, the cycling of basic materials on the planet, and energy’s capture, usage and flow. One fundamental principle in ecological economics is the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy within a closed system tends to increase over time. This implies that systems naturally progress towards greater disorder and less predictability. The second law of thermodynamics applies to nature and ecosystems.

An ecosystem experiences entropy but is sustained by energy gathering. Ecosystems need a constant supply of energy to synthesise the required molecules and to counteract the universal tendency toward increasing disorderliness.

Beyond the environmental economic calculation of the value of resources harvested and of financial rents obtained from Nature, there are non-financial benefits and services. We value these non-financial benefits, as individuals and collectively, but we normally don’t consider them in accounting systems.

On an individual level, non-financial benefits include an affinity for natural environments, such as access to national parks and the associated mental health benefits. Collective benefits or public goods include Nature's role in maintaining a stable environment, sequestering carbon, providing pollinators for agriculture, being a reservoir of useful molecules for medicine or materials and structures for inspiration, creativity and technological innovation.

The local biome and ecosystem can be part of a person or group's identity and bring social bonding and mental health benefits. The Dasgupta Review delves deeply into the various ecosystem services we derive from nature. It explores ways of thinking on incorporating those services into our “economic system” by considering their tangible values to humanity. (This is an abridged version).

Chapter 2: What do I need to do?

In the rapidly evolving domain of sustainable finance, the regulatory and voluntary reporting landscape remains in flux. As of March 2024, UK asset managers and owners face no specific mandates for reporting on nature or biodiversity metrics. Yet, inspired by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) has emerged as a promising new initiative. Announced in July 2020 and officially launched the following year, TNFD has been meticulously crafting a comprehensive framework for corporations and financial institutions to standardise reporting practices. By March 2023, their final beta framework was introduced, with 1,000 organisations pledging to conform to their standards.

TNFD

For investors, the introduction of TNFD presents both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, it aims to provide a more structured approach to data reporting, potentially leading to more uniform data points over time. This structural framework serves as a guide for investors to report to stakeholders and enhances the analysis of portfolio companies. On the other hand, the transition to uniformity might be gradual due to the introduction of a wide array of metrics — 34 core metrics, 70 sector-specific metrics, and 29 voluntary metrics.

Initially, this diversity may lead to heterogeneous data, reflecting the complexity of nature-related financial disclosures. However, the direction set by TNFD is promising, indicating a move towards standardisation and homogeneity in reporting over time. The UK's consideration of making TNFD reporting mandatory, akin to TCFD mandates, underscores the significance of this shift.

EU

Beyond TNFD, the landscape of reporting frameworks and requirements is broad, especially within the EU. Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) indicators, such as PAI 7, spotlight investments in companies affecting biodiversity-sensitive areas. Moreover, the EU is stepping up efforts to require corporate disclosures on biodiversity and ecosystem impacts. Globally, initiatives are being launched to enhance transparency in nature-related matters, with countries like France (Article 29 of the French law on Energy and Climate) and India leading by example through specific disclosure requirements.

Navigating this evolving terrain poses a considerable challenge for investors, who must keep abreast of changing standards and expectations. Despite a strong interest in nature and biodiversity topics among professional asset managers, many adopt a cautious stance, awaiting clearer market directions. Conversely, proactive engagement with emerging data standards is seen by some as essential to gaining proficiency and insight ahead of regulatory enforcement. The trajectory is clear: stakeholder expectations for comprehensive and transparent disclosures on nature and biodiversity are on the rise.

Chapter 3: Who is out there to help and guide?

The rapidly progressing formalisation of ESG in recent years has not only accelerated the changing expectations of business accountability but has also highlighted its societal role. Data disclosure has become imperative for businesses that try and narrate their story to capture opportunities, mitigate risks, attract investments and comply with regulations. To help with the disclosures, various stakeholders have stepped up efforts in sustainability initiatives and the phrase ‘alphabet soup’ reflects the abundance of reporting frameworks, principles and standards, certification bodies, and ESG specific ratings agencies and indices all in the mix.

While these initiatives have helped shape the disclosure landscape, the abundance and complexity of the acronyms have put a damper on their main purpose.

This section helps make sense of the ESG alphabet soup by defining and categorising some of the commonly used standards, frameworks, and indices.

Frameworks.

Frameworks provide principles and guidelines for how information should be disclosed. Below are some of the widely used regulatory and voluntary frameworks.

Methodology for measuring and assessing greenhouse gas emissions associated with a product or organisation.

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

EU legislature aimed at enhancing how businesses report on social and environmental impact activities.

EU regulatory framework requiring large businesses to report on their ESG data.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The 17 global goals of the UN for addressing global challenges and promoting sustainable development.

Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (SECR)

UK framework and legislation that requires large companies to disclose their energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

UN Guiding Principles Reporting Network (UNGPR)

Global guidance for companies to report on respect for human rights.

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC)

A reporting framework with 10 principles to guide CSR in line with the UN SDGs. The largest corporate sustainability initiative used by businesses around the world.

STANDARDS AND BOARDS

Standards guide organisations on what they must report. They work hand in hand with frameworks. While frameworks aim to provide the big picture, standards provide the details. We list the most common ones below.

Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB)

Global organisation setting climate-related disclosure standards for corporates.

CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project)

Global environmental disclosure system enabling companies and governments to measure and manage environmental impacts.

Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF)

Collaborative initiative with a focus to manage climate related financial risks.

Corporate Reporting Dialogue (CRD)

A group of corporate reporting providers working together to achieve coherence and comparability between reporting frameworks and standards.

European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)

EU mandatory standards for companies reporting under the CSRD.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol

A Collaborative initiative to provide globally recognised accounting and reporting standards for measuring emissions.

GRESB

International benchmark for ESG performance in real estate.

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

Sets widely used standards and guidelines for businesses to support organisations with sustainability reporting and communication.

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)

Global accounting and sustainability disclosure standard developed by the ISSB and IASB.

International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB)

Global board responsible for setting sustainability reporting standards.

International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labelling Alliance (ISEAL)

A global organisation for sustainability standards with codes and credibility practices.

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB)

SASB Standards allow businesses to track and communicate financially material sustainability actions to investors.

Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi)

Defines and promotes best practices in science-based environmental impact measures by corporations.

Science-Based Targets Network (SBTN)

SBTN builds on the SBTi carbon targeting to target biodiversity and nature targeting.

Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)

EU regulations to guide the ESG disclosures of financial institutions to improve transparency and reduce greenwashing.

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TFCD)

Task force that develops recommendations for climate-related financial disclosures.

Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)

Global task force focused on developing guidelines for disclosing financial impacts related to nature-related risks and opportunities.

Natural Capital Protocol (NCP)

Decision-making framework to guide organisations undertaking natural capital assessments. NCP enables organisations to identify, measure and value their direct and indirect impacts and dependencies on natural capital

Comparison of Nature-related assessment and disclosure frameworks and standards (UN environment programme)

This report, co-authored by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) and the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), provides an overview of the key methodological and conceptual trends among the private sector assessment and disclosure approaches on nature-related issues. It provides comparative research on seven leading standards, frameworks and systems for assessment and disclosure on nature-related issues

Index Providers

Index providers aggregate data into metrics to represent a particular market or strategy. Indices allow investors to track the performance of companies following certain ESG criteria.

Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes (DJSI)

The DJSIs are a set of benchmarks that assess companies on their sustainability.

FTSE4Good

Stock index based on sustainability credentials and ESG practices.

References

APPENDIX